28: .22/27

by Nathaniel Berry

Hopkins gave away his .22 caliber Colt automatic pistol to Nick… It was to remember him always by.

—Ernest Hemingway, Big Two-Hearted River

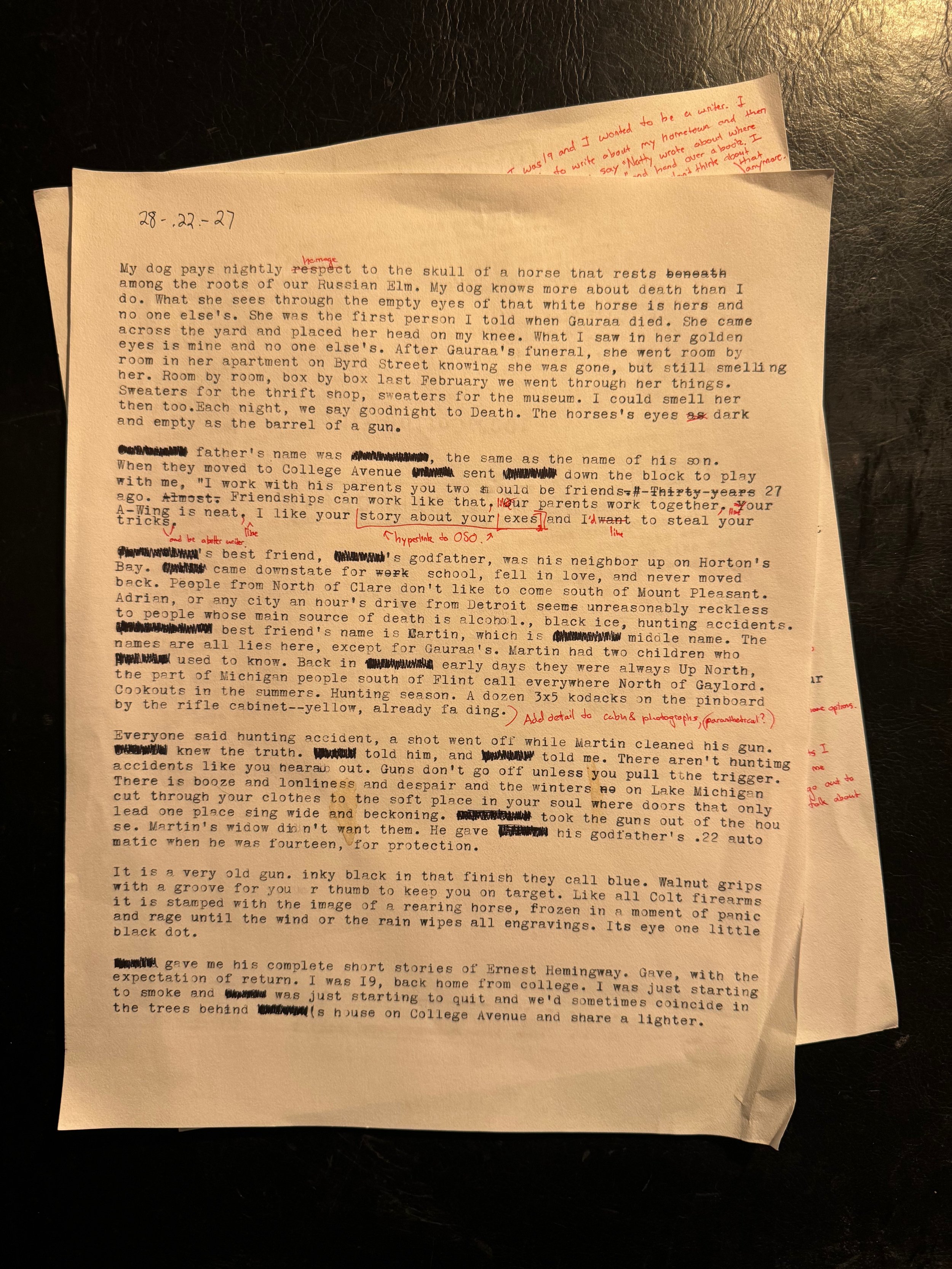

It is a very old gun, inky black in that wet-looking finish they call blue. Walnut grips with a groove that meets your thumb halfway. Like all the old Colts, it is stamped on the side with the image of a rearing horse, frozen in a moment of desperate pride or violent panic. Its eye is a tiny black dot that meets you halfway on a sleepless night.

Martin’s father, Jake, gave me his complete short-stories of Ernest Hemingway—the Finca Vigía edition paperback––with the expectation of return. I was nineteen. It was summer. I was home from college and I wanted to be a writer. I was just starting to smoke and Jake was just starting to quit smoking, and drinking, and we’d coincide sometimes in the trees behind their house on College Avenue and share a lighter. Read “Up In Michigan,” he told me. It’s not a very pretty story, but it’s about where I’m from. I was going to be a writer and I was going to write about my hometown, and have someone say Natty wrote about where I’m from, and hand over a paperback with a broken spine to some kid who was going to be a writer too. I can’t remember the last time I thought like that.

The last time I saw Jake we were Up North. I was twenty-seven, and I had finally read his book. We were hunting, which is to say I was reading paperbacks in a pop-up deer blind while Martin and his father and cousin did the real hunting. We took another layer of clothing off each day as the November heat turned the frost on the fens to a mist that blanketed the deer who were sleeping comfortably in the November heat, we were certain, just beyond the hills.

Run into Boyne and get some ice, Jake told me, while he and Martin were stringing up Martin’s deer (and, of course, Martin finally got one: Martin who was always serious, and who knew better about guns.) We put bags of ice in the body cavity to keep the meat from spoiling. They’d never had to do that before. I’d bought the last ice they had in Boyne City. I think you ought to do a European Mount, Jake told Martin over dinner. That is where you leave the head of the deer you’ve killed somewhere the bugs can get it. After a season all that’s left is a skull.

My dog pays nightly respect to the horse skull that rests among the roses growing between the roots of our Siberian Elm. White skull with empty eyes dark and bottomless as the barrel of a gun. My dog knows more about Death than I do. Whatever she sees through the empty eyes of that sun-bleached horse is hers, and no one else’s. My dog was the first person I told when Gauraa died. She came across the yard and placed her head on my knee. What I saw in her golden eyes is mine, and no one else’s. After Gauraa’s funeral, my dog went room to room in her apartment in Richmond, knowing she was gone, smelling her everywhere, searching for her anyway. Room by room, box by box, last February we went through her things: sweaters for the thrift shop, sweaters for the museum. Playmobil penguins. Quarters in an Altoids tin. Smelling her everywhere.

Martin’s father’s name was Jake, same as Martin’s son. When they moved to College Avenue, Jake sent Martin down the block to play with me. I work with his parents, he told him. You two should be friends. Twenty-seven years ago. Deep friendships can endure on the shakiest foundations: like our parents work together, like I like your story about your exes and I want to be a real writer like you, like we loved a woman who is gone, and something must be done about her sweaters, her book, her magazine.

Jake came downstate from Horton’s Bay to study history at Adrian College, leaving his best friend Matthew behind. He fell in love, got a job at the college and never moved back Up North: that part of Michigan that anyone who lives south of Flint calls anywhere north of Clare.

It is the way of fathers to reincarnate their childhoods in their sons, and the way I spent my summers in New Hampshire, haunting all the old spots with my dad and never quite learning how to sail, Martin spent his with his father and Matthew Up North, at the deer camp up on Walloon Lake: low shingled cabins, fieldstone chimneys, pole barns, old junker trucks rusting through, a dozen 3x5 Kodaks on the cork-board by the rifle cabinet: orange-clad relatives posing awkwardly with dead deer, yellowing, curling, fading. Jake’s family and Matthew’s crowded into bunk beds, sleeping on couches in front of fans. Cookouts. Repairing deer blinds. Martin up and half-sleeping, hearing his father and godfather plan for the next hunting season.

They said it was hunting accident, a round discharged while Matthew was cleaning his gun. But Martin knew the truth, because his father had told him, and I know because Martin told me, one summer when we were in Jake’s garage, rounding up empty beer cans for their ten-cent deposit. There aren’t all that many hunting accidents. Guns don’t go off until you pull the trigger. A drink or a gun will not help the feeling that every good thing in life is something that already happened to you. The winters on Lake Michigan used to cut through to your union suit and now the summers are hot and muggy, they start earlier each year, burn longer into the months you used to count on for snow. Jake drove up to Horton’s Bay to take possession of his best friend’s guns, gave Martin his godfather’s Colt .22 automatic. Martin kept it in a plastic case with a sticker on the front from the Adrian High School Cross Country Team logo. Winged shoes and a Maple Leaf, which he left behind went he went off to college.

Martin found his father next November dead in the front seat of his pickup. He’d driven deep into the woods with a .22 and a bottle of something that was empty by the time Martin found him. I never asked him what any of that looked like. I’ve never tried to guess. But I know the feeling that everything good that was ever going to happen to you already happened, and the summers are doomed to get warmer, and your friends are bound to die. At Jake’s visitation, at the funeral home next to the Family Video, I wondered who had heard it was a hunting accident. People were telling Martin how much he looks like his dad. He does, but that’s beside the point. What kind of thing is that to say? What is wrong with everybody? A street of widows, he called College Avenue. A ghost on every corner, I told Loren. Do you mean Adrian or New York? she asked, and I couldn’t remember what I’d meant.

I never tell him how much he looks like Jake, just like he never tells me how much I look like my own father. I never ask if the .22 Martin issued me for protection during the first few weeks of the pandemic is the one he found in his father’s hand or not. I keep it in the drawer with the typewriter I got Gauraa on her 27th birthday. I keep the tine from the deer Martin shot that last time up in Walloon Lake, and the copy of Jake’s Finca Vigía edition with the brochure from his funeral for a bookmark. And these, like fading Polaroids and thrift-store paintings, the old GE clock radio, the mug with the sailboat from New Hampshire, to say nothing of every book I ever borrowed and never returned will someday be someone else’s to put in a box. Thrift store. Museum.

I’d gone to the Chelsea Hotel while Robby was at work, where Gauraa and I had always promised we’d meet after she, or I––it never mattered who––swooped up that Cat Person advance; and we’d promised to drink at the bar, and we’d promised to sing songs in the suite until the sun would rise like victory over the water towers on all those little rooftops in Manhattan. I told the bartender I was visiting a friend, a woman whose magazine I’d worked for in the best and most terrible years of my life. My friend was a writer, I told her. She was more talented than me. Her heart was a legend. I wrote stories for her about the town I’m from and about the people who lived there, and I was going back again, very soon, to write the last one.