Laura & Gus

Maple City Dispatch: stories from the former “Fence Capital of the World,” Adrian, MI

by Nathaniel Berry

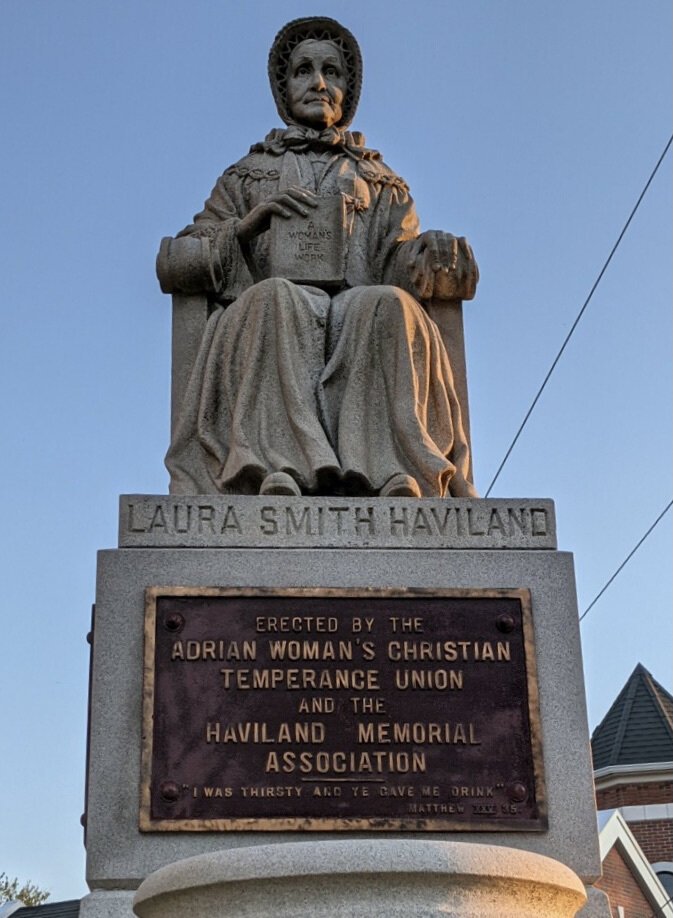

Laura Haviland sits in granite outside the Lenawee Historical Society Museum. Her face betrays embarrassment for anyone who would spend money on a statue. A committed abolitionist who lived a long life of hard and heroic work, she died trusting the work left undone into the hands of the future. There’s a drinking fountain at her feet—I was thirsty and ye gave me a drink—from the Book of Matthew, inscribed in bronze above. The fountain has been disconnected.

A midwestern Wesleyan who dressed in black every day of her life, Laura would have been made deeply uncomfortable by a statue raised in her honor. She and her husband came to the Michigan Territory to join the anti-slavery cause, and Laura continued her work through almost unimaginable personal tragedy. An outbreak of erysipelas killed her parents, her husband, and her youngest child all in the same year, leaving her to raise her seven surviving kids alone in what was still, essentially, the wilderness. Raising seven kids in a sixteen-by-eighteen-foot cabin would have been accomplishment enough for anybody’s life, but Laura’s beliefs compelled her to do more than simply survive. She believed certain simple, self-evident truths: that human beings deserve dignity, freedom, and prosperity. She believed, like William Lloyd Garrison, that the American Constitution was a pact with the devil, an agreement with hell because it codifies and enshrines the institution of slavery. Her beliefs estranged her from her neighbors and her church, and made her into an outlaw.

Laura became a superintendent of the Michigan Underground Railroad, working under radical abolitionist George DeBaptiste, who ran a fleet of smuggling vessels on the Great Lakes. She traveled South to meet strangers by the roadsides of Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and brought them North to DeBaptiste, who transported them to Canada, beyond the reach of the American justice system. Laura made more trips South than she ever bothered to count, and made more mortal enemies than she could name. Once, she and her son were held at gunpoint by Tennessee slaver Thomas K. Chester. When they managed to escape, the Chesters put a $3000 dead-or-alive bounty on her head, circulated broadsheets with her description and home her address in Raisin Township. Chester wrote to Laura, promising to name the next infant born into slavery on his plantation after her dead child. Laura continued traveling South in disguise, until she was charged with violating the Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law designed to imprison activists if they so much as offered a cup of cold water to a refugee. Laura bribed a judge and escaped to Ontario on one of DeBaptiste’s boats.

After the Civil War, she came back to Lenawee County and ran a school and orphanage for formerly enslaved children. Originally, the school was funded by the Freedman’s Bureau, but when the moderate Northern Republicans compromised with revanchist Southern Democrats, the Freedman’s Bureau schools were defunded, the orphans thrown (literally) onto the street. Laura spent the rest of her life raising money to re-open the school. The prospect of housing and educating Black kids earned her few friends among her neighbors in Lenawee County, but after she was safely dead, they were happy to pitch in and make her a statue.

We make monuments to people we aspire to be like. We like to imagine that if we lived in the bad old days, we would have all been Laura Havilands and George DeBaptistes. The same way every old theater is said to be haunted, every old house in Adrian contains some peculiar upstairs closet, some alcove in a wet basement that the owner swears was a hiding place for the Underground Railroad. These stories are shaky connections to the parts of our history we want to emphasize. The Klan robes—like the ones Martin’s dad found in a corner of a neighbor’s carriage house—are downplayed as outlying anachronism, if they’re considered at all.

If Laura’s statue stands to remind us who we’re supposed to be, the Gus Harrison Correctional Facility stands nearby to remind us who we still are. An enduring monument to the consequential and unremarkable life of prison bureaucrat Gus Harrison, the medium-security facility sports double chain-link fences, razor-ribbon wire, and two gun-towers. It can imprison over 2000 men. Within, prisoners are fed undercooked food, prepared in unsanitary conditions by the notorious private contractor Aramark, and are housed in groups of eight people, in eighteen-by-nineteen-foot rooms. Truth-in-sentencing laws, like those in the Joe Biden-authored 1994 Crime Bill, keep non-violent offenders behind bars even after they’ve been granted parole. In Adrian, at least 1400 prisoners contracted COVID-19, and at least 6 died. These deaths and infections are not factored into Lenawee County’s official total for infections and deaths. This is because you’re not supposed to think about how many of your neighbors live and die behind bars, just a stone’s throw from where Laura Haviland lived and died in the struggle to end slavery.

Prisoners must work in Michigan at least 5 days a week. This can be increased to 7 days per week at the discretion of the warden. In Michigan, a prisoner is paid $1.24 per day for skilled labor, and is eligible to make $1.54 per day after two months of satisfactory work. They can receive an extra $2.00 per day if the work is deemed especially difficult by their warden. The state manual suggests that things like cleaning bloodborne pathogens, or working with high-voltage currents, constitute the kind of work a warden might deem especially difficult. Inmates in Michigan make mattresses for prisons and hospitals; uniforms and tactical vests for police officers and prison guards; high-visibility vests for maintenance crews and crossing guards; road signs and license plates. They make American Flags. Prisoners, boasts the Department of Corrections website, sew the American Flags with pride.